Last year’s global temperatures set an astonishing record. It was 1.75 degrees C above the long-term average. It takes an inconceivable amount of energy to raise the temperature of our entire planet that much over an entire year.

Temperatures in January and February this year have continued this trend. As I write this, there are record-breaking heatwaves in South America, Central Asia, and the Middle East.

We are in a bigger mess than we realize if the rate of global warming is accelerating. Scientists I talk with are worried, but some say the increase is high but not crazy high.

However, there is some new data that indicates we may be on the path to the crazy side of high temperatures.

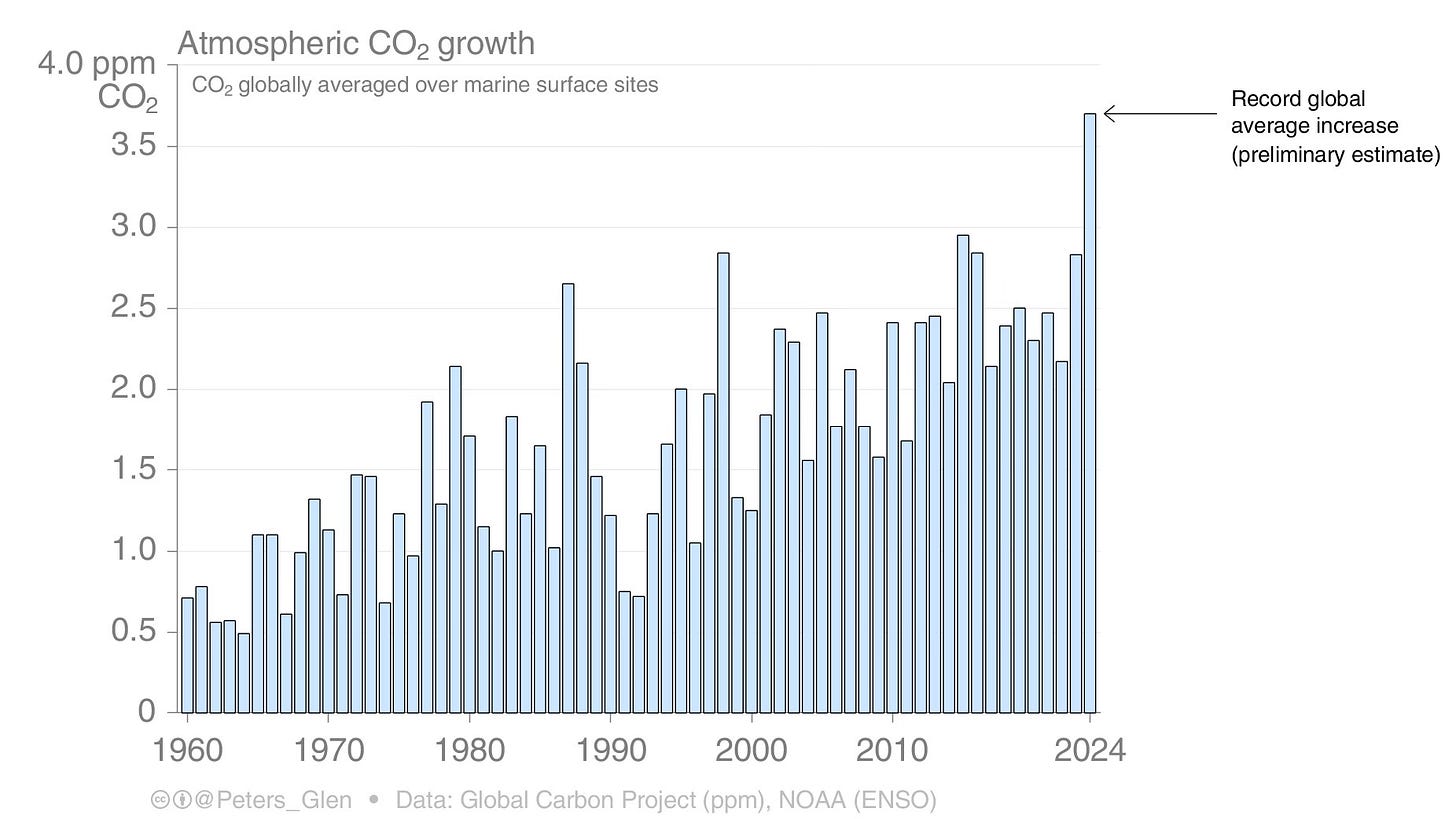

Here’s what Glen Peters, a senior scientist with Norway’s Center for International Climate Research and one the world’s leading experts on climate had to say about the graphic above on Wednesday:

Preliminary data suggests that the global average increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration in 2024 will be a record.

Not just a little record, but 25% higher than the previous record.

If the data holds, it would imply a rather substantial decrease in the land sink (on the assumption the ocean does not change much).

Let me explain:

Our carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels in 2024 were barely higher than the emissions we added in 2023 or 2022. Despite relatively stable emissions, the new data shows the amount of CO2 added to the atmosphere in 2024 was 25% higher than what was added in 2023 or 2022.

So what’s going on?

Oceans, forests, wetlands, and other natural systems act as carbon sinks, absorbing about 56% of humanity’s CO2 emissions over the past 50 years. We’re extremely fortunate that nature has been providing this CO2 reduction service, otherwise we’d be already be suffering with catastrophic levels of warming.

Need-to-Know: Our luck may be running out.

A couple of years ago, there was some evidence that forests and other land-based carbon sinks aren’t taking up as much carbon as they did in the past. For example, deforestation, along with higher temperatures, droughts, and wildfires, is reducing forest cover and reducing the forest carbon sink.

Wetlands are also drying out in hotter temperatures, reducing their ability to soak up carbon.

Although not an active carbon sink, we’ve seen increased carbon and methane emissions from permafrost melt due to warmer temperatures. That’s not helping.

Unfortunately, the data showing the 25% rise in CO2 in 2024 is the clearest evidence to date of declining carbon sinks.

Need-to-Know: We need to protect Nature to protect ourselves

Any decline in natural carbon sinks means we need to cut emissions faster or risk even hotter temperatures, which could trigger dangerous climate feedback and raise global temperatures even higher.

We also need to protect the remaining carbon sinks and carbon stocks in ecosystems. Afforestation programs and building new carbon sinks in agriculture can help bolster natural carbon sinks.

Until next time, be well.

Stephen