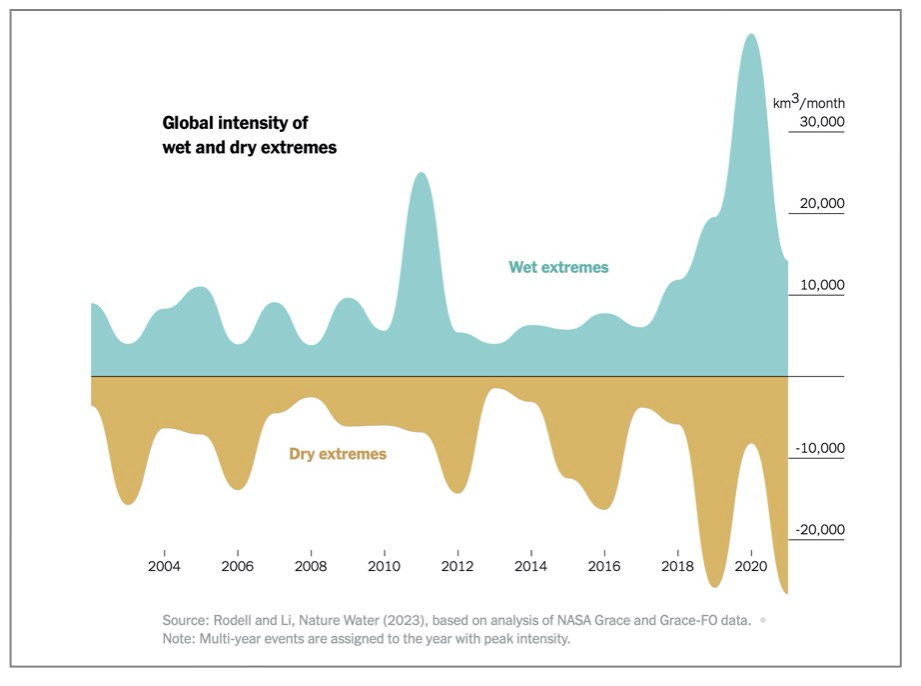

The duration and severity of droughts and floods have increased worldwide since 2002. These extreme events have increased by 25% in recent years, according to 20 years of NASA satellite data measuring fluctuations in water above and below ground.

Need-to-Know: Climate change increases the odds of extreme drought and flooding

This is probably not a big surprise to anyone following news reports on weather disasters worldwide. Three things explain why floods and droughts are getting worse.

The atmosphere holds more water.

Warmer air can hold more moisture: 1 degree C warmer = 7% more moisture or water vapor. When we get 1.5 degrees C warmer (and we will soon) our atmosphere will hold 10% more water. However, the amount of moisture in the air over any one particular area will vary tremendously.

Evaporation rates over land have increased.

Air over land areas has become increasingly warmer and drier based on 40 years of global data. (See Need-to-Know: A Fundamental Change to the Earth’s Water Cycle is Underway.)

The oceans provide most of the water vapor found over land.

So where are droughts and floods more likely to occur? Here’s a couple of big trends based on an analysis of decades of observations published last spring in the journal Nature Water:

— The tropics are experiencing more intense wet spells.

— Continental regions are seeing a trend toward drought.

Need-to-Know: Flash droughts are happening more often

There has also been a big increase in flash droughts—droughts that form over just a few weeks with little warning. South Australia, North and East Asia, Europe, and the western coast of South America saw the most significant increases, according to a study in the journal Science.

Higher rates of evaporation are the primary driver of flash droughts and these will become more common.

Need-to-Know: The world’s lakes and reservoirs are drying up

One impact of all this drying is a decline in water levels in more than half of the world’s largest lakes and reservoirs as evidenced by Lake Mead’s infamous bathtub ring. These declines amount to roughly 22 billion tons of water per year for the past few decades.

Lakes hold 87% of Earth’s surface fresh water and are a crucial source for drinking water, irrigation, hydropower production, and industrial uses. So, these falling water levels are not good.

From too little water to too much.

Remember that big flood in Pakistan almost a year ago? One-third of the country was underwater, and more than a million homes were destroyed or damaged, along with thousands of kilometers of roads and more than 28,000 schools and health clinics damaged. Over 30 million people were affected. (The Guardian has an article on how things are today— it’s grim.)

There is no way to recover from that scale of devastation—for any country.

The cause of all this was weeks of rainfall totaling 700% above normal in some places.

Need-to-Know: Rainfall is increasingly torrential

Extreme rainfall was the first well-documented impact of climate change some 20 years ago. What often happens is that a month or months of precipitation comes down like a waterfall over a few hours or days. Flooding is inevitable and unstoppable even for the most expensive infrastructure.

The only way to win against water is not to fight.

— A.R. Siders, University of Delaware’s Disaster Research Center water expert.

So what to do, aside from cutting emissions from fossil fuels as fast as possible?

National Geographic Explorer Erica Gies, a friend and an excellent journalist, has some answers in her new book Water Always Wins. .

The overarching solution Erica says is conserving or repairing natural systems or mimicking them so they can buffer us from bigger rainstorms and longer droughts by absorbing and holding water.

Nature-based approaches to water management brings a number of benefits including protecting and increasing biodiversity while reducing floods and droughts at a lower cost, compared to building concrete infrastructure.

Conventional infrastructure is largely about controlling water and speeding it away as fast as possible. That limits the replenishment of both soils and groundwater and reduces wildlife habitat.

Need-to-Know: Coping with extreme water requires collaboration with nature, not control

The key to coping with increasing extremes of flood and drought is to find ways to slow water on land to allow the natural water-land interaction to take place, she writes.

In this era of extreme water, a shift in mindset is needed towards collaboration and partnership with water rather than control, Erica says.

Among the most important things humanity can do in coming years is to shift from trying to control nature to learning to be a partner. And learn to be far better at collaborating with each other.

Until next time. Be safe.

Stephen

Need to Know: Science & Insight is my personal newsletter that looks at what we Need-to-Know at this time of pandemic, existential crisis of climate change and unraveling of nature’s life supports.